On the second day after our arrival in the land of the Holy One, we were welcomed to St. George's Cathedral in East Jerusalem by Archbishop Suheil Dawani. He reminded us that his ancestors were present at Pentecost, when the Church was born (see Acts 2:11) and Christianity spread out from Jerusalem. And then he used the phrase "living stones" to speak of this continuous Christian presence in this place. It's a reminder that missionaries from the west don't need to bring the Gospel to this place; this is the home office. (See the rest of Acts.) But the need to be sure there are "living stones" even now is to be sure that these old churches don't become merely museums but that there continue to be vital Christian communities in this land.

I've been reflecting on this phrase since that first night and trying to pay attention throughout this pilgrimage to those "living stones." Without a doubt, first and foremost there is Iyad Qumri - our Palestinian Christian guide. I mentioned in an earlier post that I first met Iyad's wife at St. George's College nearly a decade ago, and then met him when I was here three years ago with the brothers of the Society of St. John the Evangelist. Iyad is a businessman and a layperson. But he also sees his work as ministry. He works exclusively with Episcopalians and in addition to being a wealth of knowledge about the sites; he is committed to telling the story of the Palestinian Christians of this land. He is surely a living stone here and a witness to the risen Christ.

One of of the other things that Archbishop Dawani said on our first night was that Jesus was a teacher and a healer. He went on to say that the Church, especially here, must be committed to education and healthcare if we mean to be his followers. The needs for both are very great. While Christians are increasingly a small minority in this land and Anglican Christians a small portion of that small minority, the Anglican presence in education and healthcare is huge. I think it's important for Episcopalians to know that our Good Friday offering, across The Episcopal Church, goes to do this important work here to serve neighbors in the name of Christ.

Today we visited one such place: The Jerusalem Princess Basma Center - something like a Shriners Hospital in Jerusalem. The work they do is nothing short of miraculous. That work is part of what it means to be following the Way of Love. It is also about embodying hope in a land that can feel discouraging. It was inspiring to be there and it was also gratifying to feel that we are, in some small way, a part of that work with all of the "living stones" who work there.

On the Second Sunday of Easter we worshiped at Christ Church (Anglican) in Nazareth. There we were greeted by a dedicated and enthusiastic young priest named Father Nael Abu Rahmoun, who told us he identifies as Arab, Palestinian, Christian, Israeli. Holding all four of those parts of his identity together is not easy, but he told us without one of those words he cannot be true to who he is as a child of God.

What really struck me the most, however, as he spoke with us is how familiar the story of his congregation is. They were struggling before he came but his energy is helping some new and exciting things to happen. Even so, he is aware that growth can't be about his charismatic leadership, but about empowering lay people to share in this work. They have a building in need of lots of repairs and a budget not big enough to do all of that work. He spoke about the need to focus on mission in the neighborhood. And about building ecumenical and interfaith partnerships. I could have been just about anywhere in the Diocese of Western Massachusetts as he spoke about the joys and struggles of parish ministry in this time. I leave here committed to keeping him, and his welcoming congregation, in my prayers.

I don't know if that's enough. But I am grateful for the witness of these living stones and these ministries that make a difference in people's lives. I'm grateful for the work of the Anglican/Episcopal Church in this part of the world and their commitment to strive for peace, and to work for justice - without which there is no peace.

Just yesterday, my boss, Bishop Doug Fisher, asked me how this pilgrimage was different from my previous times in this holy place. This is my fifth time here - first when I was an undergraduate in college and now four times in the past decade. I told him that my head didn't hurt as much this time. There is so much to "take in" when coming here - beyond just a lot of new information. It can feel emotionally exhausting. It's complex and most of us - or at least I - like to simplify things. So it can be exhausting the first or second or even third time here. I'm now returning to semi-familiar places. You see things in new ways even if you aren't learning new information. So my head doesn't feel like it is going to explode with all of this input.

But on further reflection, I think what is different this time is that I'm even more deeply aware of these "living stones" who are members of the Body of Christ, who are committed to doing the work God has given them to do. I didn't add a picture of the brewery in Tabeh above but I could have. They, too, are doing the Lord's work because they are coming back to the West Bank after having gone to college in the United States. They are committing themselves to economic development and like Jeremiah buying a field in Anathoth (see Jeremiah 32:9 ) and in so doing they are, like Jeremiah before them, acting in faith and hope.

This is what living stones are called to - in this and every land. To act in faith. And hope. And love. And to not lose heart.

Tuesday, April 30, 2019

Friday, April 26, 2019

The Solace of Fierce Landscapes

This morning, our group of pilgrims left East Jerusalem at 5:30 am to head out into the Judean Desert, to the Wadi Qelt. There we watched the sun come up, and we celebrated Holy Eucharist together.

Years ago I read a book by Belden Lane, entitled The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Exploring Desert and Mountain Spirituality. It's an extraordinary book that I commend to you. Being in the still, cool morning air of the desert as the sun rose brought that book immediately to my mind again. There is a sense of peace and solace that does indeed come from the stark beauty of such a place. Lane writes:

"There is an unaccountable solace that fierce landscapes offer to the soul. They heal, as well as mirror, the brokenness we find within."

I was in this very same place three years ago, almost to this very day, with the Fellowship of St. John the Evangelist, when I was asked to preside at the Eucharist. Today, a retired priest of our diocese, Annie Ryder, presided. She reminded us in her sermon of Elijah, who had his own encounter with fierce landscapes. (See I Kings 19:11-13.) He did not find God in the wind, nor in the earthquake that followed, nor in the fire that came after that. Rather, the Lord was in the "still, small voice" that followed all of the drama. We didn't have the wind or earthquake or fire today - but many of us did experience that still, small voice and a sense of awe and wonder in this quiet and beautiful place. It is indeed a stark and even fierce landscape, and yet it also brings the solace that Lane speaks of so eloquently in his book.

In this land, especially, one becomes aware of the trauma that has been experienced on all sides of the conflict here. Being afraid takes its toll on all of the Children of Abraham; none are spared. Being afraid reveals our brokenness. That brokenness can either be healed - so that we learn to put our trust in God - or it can be misdirected both inwardly and outwardly. Only when we are healed, however, can we possibly become instruments of God's peace, and a part of the work of God that brings peace on earth and good will to all.

In this land, especially, one becomes aware of the trauma that has been experienced on all sides of the conflict here. Being afraid takes its toll on all of the Children of Abraham; none are spared. Being afraid reveals our brokenness. That brokenness can either be healed - so that we learn to put our trust in God - or it can be misdirected both inwardly and outwardly. Only when we are healed, however, can we possibly become instruments of God's peace, and a part of the work of God that brings peace on earth and good will to all.

The Trappist monk, Charles Cummings, once said that "the desert is the weaning process in which the child comes to love the mother more than the milk." That line resonates with me and with the experiences I got to share today with my fellow diocesan pilgrims in the Wadi Qelt.

Years ago I read a book by Belden Lane, entitled The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Exploring Desert and Mountain Spirituality. It's an extraordinary book that I commend to you. Being in the still, cool morning air of the desert as the sun rose brought that book immediately to my mind again. There is a sense of peace and solace that does indeed come from the stark beauty of such a place. Lane writes:

"There is an unaccountable solace that fierce landscapes offer to the soul. They heal, as well as mirror, the brokenness we find within."

I was in this very same place three years ago, almost to this very day, with the Fellowship of St. John the Evangelist, when I was asked to preside at the Eucharist. Today, a retired priest of our diocese, Annie Ryder, presided. She reminded us in her sermon of Elijah, who had his own encounter with fierce landscapes. (See I Kings 19:11-13.) He did not find God in the wind, nor in the earthquake that followed, nor in the fire that came after that. Rather, the Lord was in the "still, small voice" that followed all of the drama. We didn't have the wind or earthquake or fire today - but many of us did experience that still, small voice and a sense of awe and wonder in this quiet and beautiful place. It is indeed a stark and even fierce landscape, and yet it also brings the solace that Lane speaks of so eloquently in his book.

In this land, especially, one becomes aware of the trauma that has been experienced on all sides of the conflict here. Being afraid takes its toll on all of the Children of Abraham; none are spared. Being afraid reveals our brokenness. That brokenness can either be healed - so that we learn to put our trust in God - or it can be misdirected both inwardly and outwardly. Only when we are healed, however, can we possibly become instruments of God's peace, and a part of the work of God that brings peace on earth and good will to all.

In this land, especially, one becomes aware of the trauma that has been experienced on all sides of the conflict here. Being afraid takes its toll on all of the Children of Abraham; none are spared. Being afraid reveals our brokenness. That brokenness can either be healed - so that we learn to put our trust in God - or it can be misdirected both inwardly and outwardly. Only when we are healed, however, can we possibly become instruments of God's peace, and a part of the work of God that brings peace on earth and good will to all. The Trappist monk, Charles Cummings, once said that "the desert is the weaning process in which the child comes to love the mother more than the milk." That line resonates with me and with the experiences I got to share today with my fellow diocesan pilgrims in the Wadi Qelt.

Wednesday, April 24, 2019

The Empire Strikes Back

|

| Our merry band of pilgrims at Herodium, Herod's Palace |

And let me get clearer still on this: I don't mind people disagreeing with MY politics! I may be wrong about many things. When I was a parish priest, and this nation was debating healthcare, I would often say that we could disagree in the parish about a particular political way forward. But we needed to agree by virtue of our Baptism that we cared about providing healthcare. (And the list goes on, clean water, food for the hungry, making sure we don't incarcerate innocent people, etc.) Why? Because we respect the dignity of every human being. And because Jesus healed people, for God's sake! He taught and healed. If his followers don't care about education or healthcare, then maybe they aren't following him very closely!

Conservatives and Progressives can and will disagree on political strategies and policies. No one party should have a monopoly on good ideas. My quarrel here is with those who think that the Bible or Biblical faith should "stay out of politics." That religion isn't meant to have anything to do with people's real lives. That is misguided and it is absolutely NOT what "separation of church and state" means.

I'd go further: it's heresy. It's Gnosticism. It has nothing to do with the scandal of the Incarnation. It has nothing to do with Biblical faith. So, to paraphrase Mayor Pete: if you have a problem with God's politics, take it up with the Creator - not me!

Faith is always political. The question is, "who's politics?" And how do we allow God's politics to deconstruct our partisan bickering in order to shape and form us to be people who seek mercy and justice?

One trajectory of a pure spirituality is the mistaken notion that one might come to the Holy Land today and expect it to be all about mild-mannered innocent Jesus. A kind of Disney version Bible-Land where we walk with Jesus and talk with Jesus and he tells us we are his own. And then we get here and we find there are people who live here and the politics are extremely complicated. Getting to Jesus means working through two thousand years of political history. And the land, while indeed holy, is contested. We may wonder if the politics is keeping us from having a real pilgrimage back in time. It can be emotionally exhausting - and human beings can only handle so much reality at a time. But, in fact, I think this is the work.

Our guide here, Iyad, is a Palestinian Christian. I first met his wife when I was here in 2010; she was working as the librarian at St. George's College. I met Iyad when he was our guide and I came with the Fellowship of St. John the Evangelist group. He knows the Biblical story well. But he also shares his own story and the story of his people. Yesterday he told our group: "I know this is your pilgrimage. But this (the Palestinian story) is part of the pilgrimage."

Every North American Christian needs to take this kind of pilgrimage to rediscover the depth and power of Holy Scripture. We need to encounter those places where we've been mis-taught. in order to rediscover the power of God's Word which is always intersecting with God's people - and especially the least among us. In so doing, we do well to remember that this land has always been contested - or at least it has been for as long as human beings can remember. It was contested even when God promised it to Abraham. It was contested when Moses looked out from Mount Nebo and it was contested when Joshua fought the battle of Jericho. Promised land or not, it has always turned out there were people living there who were pretty sure it was their land. This land may be holy. In fact, I think it is this holiness that keeps drawing me back. But it's still land. And land represents power. It's real estate. It is settled - legally or illegally - here and around the world. It's contested. And that can't be separated from Biblical faith.

So whose land is it? It turns out that's an essay question, not a multiple choice question. One might begin by saying it's God's land. But then who gets to tend it? Who gets access to clean water? These are political questions. But underneath the politics they are also theological questions about who God is or at least whom we claim God to be. And for Christians, about what it means to claim Jesus as Lord.

So when someone says, "just preach the gospel and stay away from politics" I literally don't know what they mean. I know I see through a glass darkly, for sure. I know that my politics is limited and sometimes partisan and sometimes I'm just plain wrong. But the solution isn't to avoid the questions in favor of "spirituality." It's to go deeper. It's to practice listening to one another. It's to strive for justice and peace among all people. Those who say "stick with religion" don't know how to read the Bible and honestly don't know what the word religion means.

So, for me, one of the great gifts of coming to this land is that it is so complicated. It requires us to be open, and to listen, and to ask in new ways, "who is my neighbor?"

Then when we read that "a new pharaoh arose who didn't know Joseph" (Exodus 1:8) we know that's a political observation that puts into place the events that Jews are remembering right now in Israel and around the world: the Passover. It's not about "spirituality." It's about the economy. It's about who benefits from the economy and who is being used by it. It's about the journey from slavery toward freedom - then and today. That may well be an inward journey with spiritual implications, but it is also an outward journey to the halls of power, where Moses will tell Pharaoh to "let my people go!" It may be centuries later when Dr. King preaches the same message in the Civil Rights movement but it's part of the very same story. Is it religion or politics? Yes.

The Old Testament emerges under the shadow of empire: Egypt, but later Babylon and Persia. The New Testament emerges under the shadow of the Roman Empire. And the history of this land continues under the shadow of the Ottoman Empire. And the British Empire. And the American Empire.

Ah, did the preacher just move from preaching to meddling on that last one? We want to believe that our national "self-interest" is always pure. But my experience tells me otherwise. I love my country. And I also know that here and in southeast Asia and in Central America we have behaved much like the empires before us behaved.

When we read in the Bible that it was springtime, the time when kings go to war, and David sent Joab and stayed home himself in order to check out the wife of Uriah the Hittite (a squared away soldier) (see 2 Samuel 11) we are put on alert, as readers, about the danger and corrosive nature of power. When the Babylonian army destroys the Temple or when Cyrus of Persia decides it is advantageous to let the captives go back home - this is not just history. It's history in the sense that all history is about politics and about power. About who is on top, and who is on the bottom. So that when Jesus comes along and talks about the first being last and the last being first, he's talking about putting the (political) world right.

Faith in the shadow of empire is about raising up a people - often under the radar - to name that power. And to unmask it. And to resist it. Faith is about the long, arduous journey from slavery to freedom. Next year in Jerusalem....

Faith in the shadow of empire is about raising up a people - often under the radar - to name that power. And to unmask it. And to resist it. Faith is about the long, arduous journey from slavery to freedom. Next year in Jerusalem....I'm in Jerusalem right now. This year. More particularly in East Jerusalem, at St. George's College - which was founded in the late nineteenth century by Anglican Christians. They do great work here. And they also wouldn't be here if it'd had not been for the British Empire. Life is complicated...

Yesterday we visited Herod's Palace. Today we'll be going into the Palestinian Territory, through a checkpoint beyond the wall, to Bethlehem. There we will remember how "in those days a decree went out from Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered." Herod freaked when he learned of the birth. This child threatened his paranoid lying self. Why? Because Jesus wanted to bring a truncated message to people's souls about the great beyond? And "let 'em eat cake in the meantime?"

I don't think that would have scared Herod enough to start killing children. Herod was scared because the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice and people like Jesus were not afraid of people like Herod. Jesus was not afraid to help bend that arc and he asked those who were willing to take up their cross and follow him to join him in that work. That was a radical idea when Jesus was healing and teaching and hanging out with a Samaritan woman at the well. And it still is.

Following him means a commitment to clean water for everyone. And unfortunately since even water can be commodified, that's about politics. Who gets clean water? Samaritan women. Palestinian men. The children of Flint Michigan. All the little children of the world. And when they aren't getting it, we begin by asking why...

Give us this water to drink, Lord!

There are no "spiritual" pilgrimages. There are, rather, pilgrimages into the mess and beauty of this world, among the nations. Both the powerful ones and the colonized ones. But there is, at the end, a vision of the healing of the nations. There is, in the end, a vision of people from every tribe and language and people and nation as one. See the Book of Revelation.

We live, in the meantime. Faith that seeks understanding comes back to the Bible again and again and when the scales fall from our eyes we realize it's always been about the journey from slavery to freedom. And that this is a dominant metaphor that carries all the way through both testaments. That Passover is the religio-politcal context for the Last Supper, and the foot-washing. The one who wishes to be great in this counter-insurgency must be a servant to all.

The empire will keep striking back, because this is what empires are built to do. They will seek to gain more and more and more power and to hold onto that power. At all costs.

Disciples who follow the rabbi who was fed on Torah and the Prophets agree to leave beyond the pursuit of power and instead seek justice and mercy and kindness. Not to leave politics behind but to uncover a new and more just way by following the way of the cross, which is the way of love. Eventually, we trust that this way leads to peace on earth. And good will. For all.

Tuesday, April 23, 2019

In the Garden

This is my 818th post on this blog. My first was on January 3, 2010. At the time I was the rector of St. Francis Church in Holden and preparing to attend a class called "The Palestine of Jesus" at St. George's College in Jerusalem. I was new to the idea of blogging but wanted to have a place to post pictures for parishioners and friends.

I had been to the Holy Land briefly during my junior year of college but this was my first more "intentional" pilgrimage,and as a preacher. I shared that experience a decade ago with my stepfather, Marty and my longtime friend, Chris - both pastors - and wrote about them here before my arrival at St. George's.

A lot has happened in the years since then. Among other things, Marty is now among the saints triumphant. Numerous "ruminations" were dedicated to that first pilgrimage. At the time I could not know that I'd return again in April 2016 with the brothers of the Society of St. John the Evangelist, again to St. George's but this time to the cathedral guesthouse. This program was less "academic" and more focused on spiritual pilgrimage as one might expect with monks leading. Again I wrote lots of posts. And I figured that might be my last time here.

One year ago, however, an opportunity emerged to share leadership with a rabbi friend in Worcester, Aviva Fellman, and to bring Christians and Jews to this holy land for a shared experience in dialogue toward the goal of deeper mutual understanding. I remain grateful for that time and that different experience of this place. Many more ruminations.

And so I now find myself once more at St. George's, in the Diocese of Jerusalem, again at the cathedral guesthouse. This time I'm travelling with my boss, Bishop Doug Fisher, and the retired dean of our cathedral, Jim Munroe. And 24 others, clergy and laity, from our diocese of Western Massachusetts.

Our itinerary will be very similar to the program I did with SSJE. But of course you can't step in the same river twice. I am changed - and we are a different group. Nevertheless, I think my previous posts from these past three journeys have been somewhere between a travelogue and theological reflection. I've posted a lot of pictures. My plan this time is to post less often but try to go deeper - to pay attention to what I am seeing for the first time or learning at a deeper level. That, at least, is the plan at the moment.

This morning I was up early and sat in the quiet of the gardens here. Sitting at a Christian cathedral,in a Jewish state - and listening to the pre-dawn call to Muslim prayers. This is an extraordinary place. As I work to get acclimated to this time and place - and allow my body to catch up to my mind and soul after a ten hour flight and a seven hour time change - I begin with gratitude. I love this holy land, not only as the place where Jesus once walked but as a (still) contested land where Christians and Jews and Muslims are called to help Jerusalem live into it's name as the City of Peace.

I had been to the Holy Land briefly during my junior year of college but this was my first more "intentional" pilgrimage,and as a preacher. I shared that experience a decade ago with my stepfather, Marty and my longtime friend, Chris - both pastors - and wrote about them here before my arrival at St. George's.

A lot has happened in the years since then. Among other things, Marty is now among the saints triumphant. Numerous "ruminations" were dedicated to that first pilgrimage. At the time I could not know that I'd return again in April 2016 with the brothers of the Society of St. John the Evangelist, again to St. George's but this time to the cathedral guesthouse. This program was less "academic" and more focused on spiritual pilgrimage as one might expect with monks leading. Again I wrote lots of posts. And I figured that might be my last time here.

One year ago, however, an opportunity emerged to share leadership with a rabbi friend in Worcester, Aviva Fellman, and to bring Christians and Jews to this holy land for a shared experience in dialogue toward the goal of deeper mutual understanding. I remain grateful for that time and that different experience of this place. Many more ruminations.

And so I now find myself once more at St. George's, in the Diocese of Jerusalem, again at the cathedral guesthouse. This time I'm travelling with my boss, Bishop Doug Fisher, and the retired dean of our cathedral, Jim Munroe. And 24 others, clergy and laity, from our diocese of Western Massachusetts.

Our itinerary will be very similar to the program I did with SSJE. But of course you can't step in the same river twice. I am changed - and we are a different group. Nevertheless, I think my previous posts from these past three journeys have been somewhere between a travelogue and theological reflection. I've posted a lot of pictures. My plan this time is to post less often but try to go deeper - to pay attention to what I am seeing for the first time or learning at a deeper level. That, at least, is the plan at the moment.

This morning I was up early and sat in the quiet of the gardens here. Sitting at a Christian cathedral,in a Jewish state - and listening to the pre-dawn call to Muslim prayers. This is an extraordinary place. As I work to get acclimated to this time and place - and allow my body to catch up to my mind and soul after a ten hour flight and a seven hour time change - I begin with gratitude. I love this holy land, not only as the place where Jesus once walked but as a (still) contested land where Christians and Jews and Muslims are called to help Jerusalem live into it's name as the City of Peace.

Sunday, April 21, 2019

We Walk By Faith

We

walk by faith.

There is a lot going on this morning: great hymns,

beautiful flowers, and a faithful congregation gathered to proclaim that the Lord is risen indeed. So I’ll keep this

very simple today: we walk by faith.

The empty tomb does not prove anything. He isn’t there. There is extra-Biblical evidence

that Jesus of Nazareth lived and taught and healed and died on a cross. A group

of 27 of us from this diocese, including a couple from this congregation, are

headed to the Holy Land tomorrow afternoon. We’ll walk in real places along the Sea of

Galilee and even out on a boat there. And in places like Capernaum where Jesus preached and

healed and taught. Pray for us pilgrims as we make that journey.

But when it comes to the empty tomb, we just have to

take the word of those women. There are other (and more plausible) explanations for

a missing corpse than resurrection.

The Paschal Mystery uses the present tense to answer

the Easter question: Christ is risen. Not he was risen and then went back to being dead again.

Christ has died. Christ IS risen. Christ will come again.Past. Present. Future. Christ is alive! The cross reminds us of his death and that it was a saving death but if we want to find Christ, we need to keep our eyes open in the present tense. In our daily lives, in the places where we live and move and have our being. And so we walk by faith, trying to keep our eyes open.

I ran into my former Lutheran colleague in Holden this

week at the YMCA. I told him I’d be with you all today and he suggested a

sermon title for my sermon. (Lutherans like sermon titles.) His suggestion: “Ware

is the body?”

I know. But here is the thing: those Lutherans are wicked smart theologically even if their jokes are corny. This title is exactly right and it's what I mean when I say, "we walk by faith." We find the risen

Christ, as he promised, when two or three are gathered together in Ware - or anywhere in the world where the bread

is broken and shared. In body and blood, Christ is

risen and lives among and through this gathered community that does this to

remember and to give thanks and to join in the movement he started.

We find him, as he promised, in the face of the

stranger, the prisoner, the one who is thirsty or hungry, in the face of the

immigrant or refugee. We find him in a cage on the border with Mexico. There we

see the face of Jesus. Christ is risen.

In this ministry of reconciliation, between God and

humankind, Jesus calls us to continue to do the work he began by becoming ambassadors

of reconciliation. So we find him whenever there is healing and reconciliation

and new beginnings. We find Jesus, risen, wherever love is stronger than fear. We

find him where there is forgiveness and veal piccata for everyone.

My

friends: we walk by faith. That is my sermon today. The empty tomb

does not prove anything. There are

plenty of martyrs out there; good people who die for a good cause. But we come

here on this morning not to grieve the death of another martyr but to look for evidence. To find some

clues of that Christ is alive. And there is plenty of evidence that Christ is alive if we know where to

look.

In a world that peddles in fear, we look for places of

hope. In a world where too often it seems impossible to be satisfied because we

confuse our wants and our needs and we want more and more and more – more

money, more beer, more oil, more shoes– we gather today to make Eucharist. Literally that word means to give thanks. We give thanks for daily bread. To say with our Jewish friends who are celebrating Passover: dayenu. It is enough.

In a world where people are so bitterly divided, we

gather to insist that we choose to be a people who are willing to kneel before

one another and wash feet, and to act out the love of God and neighbor not only

with our lips but in our lives. When we take this bread and eat it we begin to

become what we eat. When we drink from this cup we remember who we are. We are

the Body of Christ. The tomb is empty because Jesus is here. Now. Calling us to

be witnesses, like Peter.

Do you remember the last time we saw Peter before

today? I was with you on Thursday night and as late as then, he wasn’t sure he even wanted his feet washed. As late as the last night of Jesus’ life, Peter wasn’t

sure what it all really meant. And then Friday was a bad day for Peter. I don’t know him. I don’t know what you are

talking about. Never met the guy.

Cock-a-doodle-doo. There is a church in Jerusalem

built on the spot where the Church remembers that Peter denied Jesus the third time. It’s one of

the churches we’ll visit while in the Holy Land. It’s called St. Peter

Gallicantu – where the cock crowed. It commemorates Peter’s greatest failure. How would you like to have a church built to remember your greatest failure?

But Easter changed Peter. It changed him to become more fully the person Jesus knew him to be all along. Peter has become a witness. He's become a preacher.

But Easter changed Peter. It changed him to become more fully the person Jesus knew him to be all along. Peter has become a witness. He's become a preacher.

Peter began to speak to Cornelius and the other Gentiles: "I

truly understand that God shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who

fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him. You know the message he

sent to the people of Israel, preaching peace by Jesus Christ--he is Lord of

all. That message spread throughout Judea, beginning in Galilee after the

baptism that John announced: how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy

Spirit and with power; how he went about doing good and healing all who were

oppressed by the devil, for God was with him. We are witnesses to all that he

did both in Judea and in Jerusalem.”

Peter is preaching just a short time after Jesus

walked on the earth and we gather here two thousand years later. But we live as

Easter people in the same way Peter did and we are witnesses. We worship a God

of second chances. We do not always get it right and in fact sometimes we get

it desperately wrong. Cock-a-doodle-doo. But that’s not the end of the story. That’s never the end of the story

with our God. Because Peter now, finally, understands that God shows no

partiality. That through Jesus, all is forgiven. That we are made alive because

He is alive.

This day and the fifty days we embark on today are not

primarily about what we believe about

the resurrection in our brains. Easter is not even primarily about what we feel about the resurrection in our

hearts. Easter is about the call for us to become an Easter people and then to become witnesses, to testify to what we have seen and heard.

That can only begin once we open our eyes and our ears. Where

have you seen the risen Christ at work in your life over the past month or so?

Whether you kept the Lenten fast diligently or kind of just showed up today –

it’s all good. Because Jesus isn’t locked into the Church any more than into a

tomb. So I ask – where have you seen God at work through the risen Christ, in

your life?

The late poet, Mary Oliver, once wrote these words

that she called, “Instructions for living a life.” A six-word creed that sums up the message of

this day.

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.

In a nutshell that is Peter’s sermon today and that is

the sermon you and I are called to preach, not only with our lips, but in our

lives.

Pay

attention. I was in a Bagel Shop a week or so ago and

let me preface this story by saying, I’m not trying to shame anyone here who may

see themselves in this story. But I am wanting to offer some advice as an old

guy with grown up sons who now live in NJ and NY. I was at the bagel shop and

minding my own business and I was watching this mother and child at the next

table. My guess he was four or five – I think she was probably taking him from

there to daycare and she was then headed to work, based on how she was dressed.

But I can’t know that. In fact I know nothing about her except what I saw: as

the kid ate his bagel and she sipped her coffee, her eyes never left her phone.

She was watching it, not her son.

Now again: no judgement. I look at my own phone a lot,

especially in boring meetings. Maybe she was a pastor and a parishioner was

dying. Maybe what she was reading was a timely email from her boss that she

needed to respond to before work. Who am I to judge? But what I felt and what I

thought, was “lady, don’t blink!” Because when you do he’ll be gone and you’ll

wonder how the time passed so quickly. And maybe like that old song, Cats in the Cradle, in the updated

version he’ll be home from college and be staring at his phone and you’ll be

wanting to talk with him. But it’ll be too late because he’ll have grown up

just like you.

Pay

attention to your life. Open your eyes and your ears and

live fully present to each moment, which is gift and gift and gift and which

will never come our way again. Savor each moment of this day and tomorrow and

the next day after that. One day at a time. And then…be astonished. Be amazed and in awe at what you notice when you are

paying attention to your life and the world around you. Awe and wonder and curiosity

are all deeply close cousins to faith. I think of Moses at the burning bush and

I sometimes wonder: would I have noticed it and stopped? Or to say this another

way, how many burning bushes do I walk past in any week. How many did Moses

walk by before he finally stopped? To stop, to listen, to be still – is to be

astonished.

And when we do that, we have to tell about it. That is

what Peter is doing in today’s reading from Acts. He’s telling the world that

cock-a-doodle-doo was not the end of his story, because of Jesus. He’s telling

what he’s seen, what he’s heard, what he knows in his bones gives life meaning.

My friends – Christ is alive. That’s what we’ve come

here to sing about today and to remind each other that in this fragmented and

broken world there is also another reality unfolding: the work of the risen

Christ. Work we participate in when we give our neighbor a drink of water, or

visit someone in prison, or reach out to a friend or put down the cell phone

and see the person sitting across from us.

Pay

attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.

Happy Easter!

Happy Easter!

Thursday, April 18, 2019

Washing Feet

As Canon to the Ordinary in our Diocese, I get around.

One week I’m out in Williamstown for a Mutual Ministry Review and the next week

I’m at a Celebration of New Ministry in North Brookfield and then I’m north to

Leominister to begin a search process following the retirement of a long-time

rector.

What brings me to Ware tonight? As you know, your rector is on family leave.

I’m glad to be here with you this holy week, and I look forward to Easter

morning with you all.

In all my travels, I have yet to be in a single

congregation in this diocese that has said to me, “we are not very

friendly. We just don’t like new people, and we need to work on that.” They all say they are friendly. Many say they

are “just like a family.”

I always find that simile of family to be a loaded one, however. Families are complicated. Jesus

himself did use that language to describe his followers, but as you may recall,

when he did that he was kind of dissing his biological family. At their best, families

are where we get to be really ourselves. Not always our best selves, either. Families

have history. Families have insiders and newcomers; the newcomers are called in-laws.

And sometimes families have falling outs – people don’t speak to each other for

years. Perhaps some of you have first-hand experience with that.

The biggest part of my job is to work with

congregations in transition, looking for new clergy. It’s a rewarding and

joy-filled ministry. I love it when congregations identify a path – the path

they have discerned God is calling them to follow. And then they find a priest

who has the gifts to help them to move that way. And everyone is so happy and

excited.

But there is also a part of my job that includes

dealing with disappointment and even failure, when things go off the rails. And

conflict, as people try to deal with the gap between expectations and reality.

I see in those moments the opportunity to move from pseudo community – fake

community – to real community. To authentic community. And I think that

language of community is more helpful than family.

How do we get there? We get there by the Way of Love. We get there through honest

communication. We get there through the challenging work of reconciliation, and

healing, and forgiveness. We get there, in short, the same way that families

do. By hanging in there. By loving one another. By going to counseling if we

need to do that. By doing what it takes.

What I find, however – and I need to be honest with

you about this, Trinity. I find that sometimes when people find that a

congregation disappoints them because it’s not like the Brady Bunch and because

everything isn’t resolved and tied up in a bow as quickly as it takes to watch

a half-hour sitcom, that people leave congregations. They get hurt or

disappointed and they take their pledge and they are gone. Never to be seen

again, except maybe in the produce aisle by a vestry member where they are

happy to share how they had their heart broken. And I admit to you, this is the

part about congregations that breaks my heart – both when I was a parish priest

and now in diocesan ministry.

In one of his most powerful and memorable stories, Jesus spoke about a kid who left home and was too young or too immature or maybe just too unlucky. He got into trouble and lost everything and then had to pick himself up and head home where his dad scolded and chastised him and reminded him that this never would have happened if he’d only been a more dutiful son. You remember that story?

That is not how it goes, of course. Even if we are

more familiar with that ending in our own experiences of families. The story

Jesus told has the dad running out with open arms to welcome his son who was

lost and has now been found. Jesus’ story ends up with veal piccata for

everyone. At least for everyone who wants to come in and join the party. The

story remains open in terms of the older brother who isn’t sure that’s quite

fair and isn’t quite sure he wants veal piccata if he has to share it with that

brother of his at the same table.

So, why are we here tonight? Does it have anything at

all to do with this rather lengthy intro? This day – Maundy Thursday - takes

its name from today’s Gospel reading. Jesus gives the Church a mandatum novum: a new commandment. Maundatum – like the word “mandate.” That’s

the thing about English – a lot of word roots from other languages, especially

Latin. Jesus isn’t making a suggestion. Actually, it’s not even really new, because

it’s rooted in the Torah, rooted in the core meaning of the Ten Commandments.

Previously Jesus got the ten down to two: love God, love neighbor. Who is

neighbor? Oh yeah, it’s everybody. No exceptions.

On the last night of Jesus’ life he gets it down to

one word: love. Our Presiding Bishop, Michael Curry, likes to say “if it’s not

about love, it’s not about God.” He preaches again and again on the Way of Love.

It seems like that is really simple. Except you all know and hear all those

false teachers out there who try, in the name of Jesus, to get people to hate

those whom they hate. Or maybe more accurately, to fear those whom they fear. Love one another, Jesus says to us on

this first night of these three holiest of days. Love as I have loved you. A mandatum novum. A new mandate.

Now, I’ve known you all for a while. I know this is a

great congregation and I know that you are with me on all of this. I know you

love one another, not superficially, but really. Like a family in all of that

complexity and ambiguity and pain and joy. And I know that you show that love

for your neighbor. I’ve witnessed it first-hand next door. I know you get this

new commandment and take it seriously and that you are living the way of love,

one day at a time. With God’s help.

But I’d be remiss if I sat down now. I want to say one

more thing to you. But first I want to make a confession. I was, not too long

ago, at a gathering for denominational leaders across the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts. I was sitting next to our bishop, Doug. There were other leaders

there, too. The United Methodist bishop and members of his cabinet. The

Methodists are really hurting these days as some of you may know. The

conference minister of the United Church of Christ and they are trying to bring

together the conferences of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. That

represents a lot of change. The Lutherans

didn’t make it this year, but they were there last time around. Presbyterians.

American Baptists. Eighteen of us at tables like a U. You get this image?

And our theme was about getting stuck in the mud. And

our conference leader had put some clay on the tables, for each of us to mold.

Here is the confession time: the bishop and I looked at each other and rolled

our eyes. Well maybe I rolled my eyes and he smiled. But I know he was thinking

the same thing. We aren’t clay guys. We like baseball. We root for opposite

teams, but we like sports. And we like serious conversations. But playing in

the mud? That’s not our thing.

But we are also both obedient rule followers so we did

as we were asked. We worked with our hands and so did our colleagues. And I was

reminded once again that there is something really important about letting go

and getting out of one’s head and being in touch, not just intellectually but

in a tactile way, with the kinds of things that Sunday School kids might do.

It’s actually very helpful. It opens some things up. That’s what it was, after

all: like a Sunday School activity.

But maybe everything we need to know about the good

news of Jesus Christ, we learned in Sunday School. So, Trinity, bear with me

because I’m almost there. You ready?

I’ve been washing feet on this night for thirty years

now. I’ve heard it is not the favorite thing of some of you. In fact when I got

the email from your parish secretary about tonight she asked me if I was doing

this or “the regular.” I told her this is the regular! And that Mary and I had

talked about me doing this.

I know some of you don’t like this. That’s ok – it’s something,

I would suggest, like me and our bishop with the clay. And I told you that

story so you don’t think I’m trying to shame or embarrass anyone. I told you

that story because I know that feeling of inner resistance.

But I’ll also tell you this after three decades of

doing this: washing kids’ feet is really fun. They have no inhibitions. As with

playdough or mud, they don’t get pedicures before church. They just come. I had

one kid, one time in Holden, who came right from soccer practice with dirty

feet. Took off his shoes and muddy socks and I washed his feet. It was awesome.

His mother was mortified. I’m sure the older lady who followed him was a little

mortified too. But it was real. Just like

a family.

Adults can come up with all kinds of reasons to sit in

the pews. You have heard a sermon tonight; I hope a decent one and I’m almost

done. I’ll quiz you on Sunday to see if you heard it right. So here’s the

review: Maundatum novum – a new

commandment. Love one another. Just like Michael Curry preaches. Follow the way

of love. Become like a family, a real messy family. Just like Jesus taught us –

a community of people who seek to do the will of God and who know that the

waters of Baptism are thicker than blood. Work at becoming followers of Jesus…

But if you stay put during the next part of this

liturgy then I will wonder if you heard a single word I said. Just like I

imagine that Jesus felt when Peter said, “um…no thanks.” So I want to encourage

you, as Jesus encouraged Peter. Move through your resistance and listen to that

inner ten year old. I don’t want to let you off the hook too easily. I trust

you enough to tell you that this matters.

The foot-washing is an object lesson in love and vulnerability

and being servants to one another. It’s not theoretical. Kids get it. Adults too

often resist. We think our feet are too ugly or too smelly or that this is just

too weird. I get all of that. And even so, I invite you to put this act at the

heart of your life together. Not just this year but next year when it becomes

the new normal. The regular. Because both washing feet and having your feet

washed makes it all real.

You could even say that Jesus whole ministry, focused

on the way of love, all comes down to this final gift to the Church on the last

night of his earthly love.

Sunday, April 7, 2019

The Fifth Sunday in Lent

I was with you just two weeks ago and it is good to be

here today. If you were in Church on that third Sunday in Lent, then you know

that I’m preaching on the Psalms this season.

You may also recall that I am enjoying Robert Alter’s

translation of the Psalms because he is a superb Hebrew scholar and because that’s

the language the Psalms were written in, and because he finds a way to capture

the poetry and help us hear the words in new ways. So here is how he translates

those last two verses of the Psalm we prayed a few minutes ago, Psalm 126.

Those

who sow in tears in glad song will reap.

He walks along and weeps, the bearer of the seed-bag.

He will surely come in with glad song, bearing his sheaves.

He walks along and weeps, the bearer of the seed-bag.

He will surely come in with glad song, bearing his sheaves.

A sheaf is a bundle. Perhaps you have heard someone

speak of a sheaf of papers. For those for whom poetry is like a second

language, what the poet is saying is that grief never gets the last word. Even

when we grieve, we imagine the harvest. Joy comes in the morning. We sow seeds

of grief, with tears. But we will sing again, shouldering bundles of wheat –

because this is God’s desire for us.

Do you believe this?

It’s the Paschal mystery. It’s what we will be

entering into again in just a week as we embark on Holy Week. You can’t rush it

because life isn’t rushed. If you tell a person who is just got a diagnosis

that she has a terminal illness this, it is almost always not helpful.

Sometimes we have to hold our tongue. Even at the grave we make our song, but

sometimes are alleluias have to be sung in a minor key.

But we can be light and hope for a friend, even when

they are walking through the valley of the shadow of death. We can bear witness

to the truth that those who sow with tears will come with glad songs, bearing

their sheaves because we know how the story ends.

The poet is saying that in the end, love wins. Always.

Always, love wins. Even if not on this side of paradise. Good Friday never gets

the last word in our lives. Never. We will look into an empty tomb in just a

couple of weeks and we will know that good has triumphed over evil and that faith

has triumphed over fear. And that love is stronger than hate.

Those

who sow in tears in glad song will reap.

He walks along and weeps, the bearer of the seed-bag.

He will surely come in with glad song, bearing his sheaves.

He walks along and weeps, the bearer of the seed-bag.

He will surely come in with glad song, bearing his sheaves.

Here is the thing. We trust how the story ends. We

trust how our stories will end, by

God’s mercy. At least most days. We’ve put our trust in the living God and that

God is worthy of our trust. We trust that through the Paschal Mystery which is

to say that through Jesus’ death and resurrection, all will be well.

But most days we live in the mess that is in between. We

live in the meantime. We sow seeds in tears and yet we wonder when we might shoulder

our sheaves. We wait. But we wait in hope. How long, oh Lord?

Some of us here today are right smack dab into Good

Friday – in the midst of loss and pain and seemingly in the midst of the powers

of this world defeating us. It all feels like too much to bear. We pray for

you. We walk with you. We know that life is not easy and most of us have been

there but it does you no good to hear how we once felt. We are here to listen

to how it feels for you.

A few of us here today may be in that zone, maybe

shouldering sheaves – maybe so filled with joy and so very blessed we can

barely hold it in. And we shouldn’t. We should not hide our light under a

bushel. We love you if that’s where you are and we give thanks to God for the

abundant blessings of this life.

But I’ve been a pastor long enough to be fairly

certain that most of us are living somewhere in between on this day. We aren’t

at the foot of the cross and we aren’t yet to the empty tomb. We are living

through a kind of prolonged “Holy Saturday,” if I can say it that way. We have known

pain and loss and grief and we do trust that shouldering of sheaves is coming –

that joy comes in the morning. But we live in the meantime. We are paused at

the comma in this poem.

Those

who sow in tears…in glad songs will reap.

The waiting, the silence, sometimes the anxiety are a

challenge. Yet it is where we spend a good portion of our lives, I think.

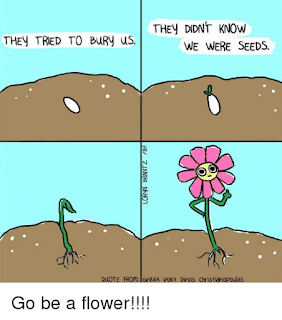

I want to share two images with you – two Facebook

memes actually. I like it that here in Southwick I can do that pretty easily. I

saw this first meme originally for 2019, but when I went looking I discovered

it was an old one redone and I’m not savvy enough to either find the original

one or to change this one so you’ll have to go with it.

In fact I think the message is the same – and not just

on New Year’s Day. It’s a choice we face every day of every week of every year of our lives. And I think it’s very much

in line with the psalm we are looking at today. The meme suggests that (in this

case flowers rather than sheaves of wheat) will come. How do we know this?

Because we are seed-planters. It’s what we are called to do. God gives the

growth. We are in the business, as Christians, of planting seeds. And then this

one, as well.

Francis of Assisi was (according to the story) once hoeing

a row of vegetables in Assisi. And he was supposedly asked, “if the world were

coming to end tomorrow, what would you do?” And Francis said, “I’d like to

finish hoeing this row of peas.” I can’t guarantee that happened. But I know

it’s true. And it’s true to Franciscan spirituality. We do the work God has

given us to do.

So, we’ve been considering a psalm which is really a

Biblical poem; a song. I’ve said some things and I’ve offered you two memes –

maybe I’ll dare even to call them icons in this context: images worth a

thousand words that invite us to go deeper. I want to conclude then with

another poem by one of my favorite poets – a pastor and farmer named Wendell

Berry. In the “Mad Farmer Liberation Front,” Berry counsels

us to “practice resurrection.” Before he gets there he writes these words:

Invest in

the millennium. Plant sequoias.

Say that

your main crop is the forest

that you

did not plant,

that you

will not live to harvest.

Say that

the leaves are harvested

when they

have rotted into the mold.

Call that

profit. Prophesy such returns.

Put your

faith in the two inches of humus

that will

build under the trees

every thousand

years.

My friends in Christ: the good news of Jesus Christ is not complicated. It’s hard, to be sure. It’s hard to live. It’s really hard to live in a world where it feels like we are traveling over rocky ground. It’s hard when we are impatient for peace and justice and reconciliation. But we live in hope. We live in hope because we are seed-planters and seed planters know that the eventually we will sow what we reap. Flowers. And vine-ripe tomatoes. The real deal. And sheaves of wheat for making bread. Daily bread, given from this good earth, gathered and broken and shared.

We live in hope, because we know that what is buried

in the earth, even our mortal bodies when that day comes, will be raised by

God. We live in the hope of the resurrection and we know that nothing, nothing,

nothing can separate us from the love of God in Jesus Christ. Nothing. Not even

death.

“This

is what we are about. We plant the seeds that one day will grow.” We

trust that God will do the rest.

Saturday, April 6, 2019

Living the Eucharistic Life

This morning I am leading a Quiet Day at All Saints Church in Worcester. For those who don't know what a Quiet Day is, the basic format is usually to gather and pray together and then in the context of the morning offer two or three brief meditations, and then give people some space to reflect in quiet, before coming back together again. At the conclusion of the morning, at least today, we will gather for a simple table Eucharist and a shared meal, and then be on our way.

I share these meditations here for those who might be interested, yet unable to join us at All Saints. Obviously you are free to use them as you wish but if you want to share in the experience of the day, I encourage you to take it slowly. My intention was to invite people to more deeply enter into the poetry of the three hymns around which these meditations are structured. Take them slowly and take each mediation one at a time, if you are able to do that - even if you don't have three hours to devote to this post.

First Meditation - Forgiveness

We – by which I don’t just mean Episcopalians but all

the Baptized – we are called to be an Easter people. That’s what Lent is for: to prepare us for that

vocation, that calling, so that we are freed to live the Paschal Mystery in our

daily lives. This day is about teasing out what that might look l like.

Easter is all about Baptism: in

the early Church Baptisms happened at the Easter Vigil. We are buried with

Christ in the waters of Baptism and also raised with him to a new life of

grace. The early Church understood this explicitly when it comes to the meaning

of Lent, which was a season to prepare catechumens for Holy Baptism and for all

Christians to remember their Baptism. It’s what your priest reminded you of on

Ash Wednesday with that invitation to a Holy Lent. Remember it?

Dear people of God: The first Christians observed with

great devotion the days of our Lord’s passion and resurrection and it became

the custom of the Church to prepare for them by a season of penitence and

fasting. This season of Lent provided a time in which converts to the faith

were prepared for Holy Baptism…

This is the vision toward

which we aspire—to live our lives in response to that truth, that seal, with

which God has marked and claimed us. But how do we move toward that vision? Not

by sheer will. Not by pulling ourselves up by our own bootstraps. Only by God’s

grace. Here may be where the Gospel is most counter-cultural and hard for us.

It’s not about us! It’s about God’s love.

Every time we break bread and

share the cup we remember our Baptism. The bread breaking and the cup sharing

were then reminders of God’s claim on us – on our being sealed and marked and

claimed by the Holy Spirit. Forever. So, living the Eucharistic life and

remembering our Baptism are basically the same thing.

In any case - I want to focus

on three movements in the Eucharistic liturgy today with three brief

meditations, as we near the end of this Lenten season and prepare ourselves for

Holy Week:

(1)

God’s forgiveness;

(2)

Our response to God through our oblations;

(3) Communion

with God and one another in this act of being fed.

At the beginning and end of

each meditation we’ll pray a hymn text that I think fits the theme of each

meditation. It is said that when one sings one “prays twice” but sometimes when

we are singing we are focused on the tune more than the text, so I want to give

us a chance to see these hymns today as prayers by praying them. The first

time, I’ll offer them on our behalf and at the conclusion of each meditation we

will pray the same hymn in unison.

So, let us pray.

Wilt thou

forgive that sin, where I begun

which

is my sin, though it were done before?

Wilt

thou forgive those sins through which I run,

and

do run still, though still I do deplore?

When

thou hast done, thou hast not done, for I have more.

Wilt

thou forgive that sin, by which I won

others

to sin, and made my sin their door?

Wilt

thou forgive that sin which I did shun

a

year or two, but wallowed in a score?

When

thou hast done, thou hast not done, for I have more.

I

have a sin of fear that when I’ve spun

my

last thread, I shall perish on the shore;

swear

by thyself, that at my death thy Son

shall

shine as he shines now, and heretofore.

And having done that, thou hast done,

I fear no more.

John Donne (1573-1631), Hymnal 140

I have long been fascinated

by Orthodox Christian preparations for Easter, which are different from what we

do in the west. This year I’ll be in the Holy Land for Orthodox Easter, which

will fall one week after we celebrate here. One Orthodox Lenten practice has

really captured my imagination. On the last week before Lent begins, on the

Sunday we would call “Last Epiphany/Transfiguration,” they celebrate what they

call “Forgiveness Sunday.” It functions a little bit like the passing of the

peace does except that every person

turns and faces every other person in

the church—not just those in the same pew. You turn to each person and say,

“Forgive me.” And the person responds: “God forgives.” Over and over again,

until it begins to sink in.

It is a profoundly

theological act. Sometimes for all kinds of reasons we cannot forgive yet. I

have been in congregations with people whom I know I’m not yet ready to share

the peace. And maybe some of you have been, too. I don’t want to feel like a

hypocrite so I just try to move in the other direction. Because if someone

turns to me who has hurt me and says, “forgive me” I may not be ready to

respond, “I forgive you.”

But we can all remember

together that God is in the forgiveness business and that God is always more

ready to forgive us than we are to forgive ourselves. Forgive me. God forgives. That sets the whole tone

for Lent, it seems to me. I think it’s a practice worth stealing, or borrowing.

But in the meantime we still

have the Confession of Sin and the Absolution which takes on even more gravity

during Lent. We confess our sins against God and our neighbor. And at the end,

the priest stands and says, “God forgives.” We also have an option in those

years when we need it for the reconciliation of a penitent which some

Episcopalians are surprised to learn is an option in The Episcopal Church.

This liturgical act of

confessing and of receiving absolution does at least two things. First of all

it tells us who God is. Both Testaments insist that God is merciful and slow to

anger and abounding in steadfast love. The absolution is structured around

those ancient truths:

- Almighty God have mercy on you.

- Forgive you all your sins.

- Strengthen you in all goodness

- Keep you in eternal life.

But second, it invites us as

the Baptized community trying to live the Easter life to forgive others as God has forgiven us. By the time we get to

Easter evening, in the Upper Room, we all remember good old “doubting” Thomas.

But what you may not recall is what happens the first time around when Jesus

comes to be with the disciples who are gathered beyond locked doors because

they are afraid. As John tells the story there is no need to wait fifty days

for the Spirit to come like tongues of fire. Jesus breathes the Spirit into the

disciples right then and there. And the work of the Spirit, he says, is that if

they forgive sins they are “loosed,” and if they retain sins, then they are

retained.

We have the choice, don’t

we? To let go, or to hold on. But at

what cost do we hold onto sins—our own or others? At what cost do we retain a

list of grievances? Retaining sins keeps us bound up, keeps us locked in the

past. In contrast, forgiveness unleashes the power of God, the Holy Spirit,

calling us to new and abundant life in Christ. It is a key movement in the

Eucharistic life, the first turn toward becoming an Easter people.

Let us pray.

Wilt thou

forgive that sin, where I begun

which

is my sin, though it were done before?

Wilt

thou forgive those sins through which I run,

and

do run still, though still I do deplore?

When

thou hast done, thou hast not done, for I have more.

Wilt

thou forgive that sin, by which I won

others

to sin, and made my sin their door?

Wilt

thou forgive that sin which I did shun

a

year or two, but wallowed in a score?

When

thou hast done, thou hast not done, for I have more.

I

have a sin of fear that when I’ve spun

my

last thread, I shall perish on the shore;

swear

by thyself, that at my death thy Son

shall

shine as he shines now, and heretofore.

And

having done that, thou hast done, I fear no more.

John Donne (1573-1631), Hymnal 140

Second Meditation –

Oblation

Let us pray:

Take my life

and let it be consecrated, Lord, to thee;

take

my moments and my days, let them flow in ceaseless praise.

Take

my hands, and let them move at the impulse of thy love;

take

my heart, it is thine own, it shall by thy royal throne.

Take

my voice, and let me sing, always, only, for my King;

Take

my intellect and use every power as thou shalt choose.

Take

my will, and make it thine; it shall be no longer mine.

Take

myself, and I will be, ever, only, all for thee.

Francis

Ridley Havergal (1836-1879), Hymnal 707

Several years ago I learned

that Bishop Bud Cederholm, who is a retired Suffragan Bishop in the eastern

diocese, was a Christian clown before becoming a priest and ultimately a

Bishop. My favorite part of the story was that his wife said as far as she was

concerned he was still sometimes a Christian clown. (I think every bishop and

priest needs a partner like that to keep him or her grounded!)

Anyway, Bishop Cederholm was

writing about Stewardship and talking about the offertory and he said they had

this routine when he was a literal Christian clown (and not just a bishop) where

at the time of the offertory one of the clowns would push another of the clowns

in a wheelbarrow down the center aisle of the church and up to the altar.

Hold that image, and imagine

yourself approaching the altar each week in a wheelbarrow. The point is

theologically important: at the Eucharist, we offer ourselves. In the older

language of the Church, as we offer some portion of our financial resources at

the altar, we sometimes say: “All things

come of thee, O Lord, and of thine own have we given thee.”

Deep down I suspect every one

of us here today knows this is true; I don’t need to convince you that this is

so. We are not our own. And yet at

another level these words are always jarring and profoundly countercultural

because most of us live – I admit that I tend to live – as if all things come

from my hard work, my ingenuity, my labor. I worked hard for all of this! And

then, of my own I share, sometimes begrudgingly and sometimes generously.

But the invitation each week

in the Eucharist is to bring ourselves to that altar: all of us, our whole

selves—the good, the bad, the ugly. Not only our Sunday best.

It used to come up for me as

a parish priest when I was doing funerals and often the family would look over

the bulletin and then sheepishly ask me why the bulletin included the word “offertory.”

And they would say, “do we really have to pass the plates at a funeral?” I

assured them that we would not be doing that. But we would still present the

bread and the wine. We would offer these gifts from God’s good earth to be

broken and shared. In fact, I’d tell them,

I hope that you will literally do that and take that job from the ushers today:

you present these gifts as we celebrate your loved one’s life. Offer

up these gifts to God and in so doing bring all of your confusion and grief and

befuddlement to the Table with you. God can handle it.

The fancy theological word,

of course, is “oblation” which comes from the old English; the root means to

offer. The Prayerbook puts it this

way:

Oblation is an offering of ourselves,

our lives and labors, in union with Christ, for the purposes of God.

The Book of Common

Prayer, “The Catechism,” page 857

Some days it comes naturally,

but other days it is hard for us to recognize and offer our gifts to God. I

find that much of the time people are truly humble about their own gifts, blind

even to what makes them such a beloved child of God. When I was in the parish,

I might tell someone, “you are a really good listener” and we need that gift on

our Pastoral Care Committee. And the person will be self-deprecating, maybe

even embarrassed. They might say, “listening isn’t hard.”

And I’d find myself saying,

“no…maybe not for you. Which is why we are having this conversation! But it is

a rare commodity as far as I can tell, and it truly is a gift you possess.” Or,

similarly, we need someone to serve on the Finance Committee which means we

need someone who is able not only to balance their own checkbook but read a

financial statement. No biggie, says the accountant. But that’s the person I

want doing that work – not the philosophy professor! And it’s holy work – in

spite of the fact that in too many parishes, too many clergy minimize that

calling as if being chair of the outreach committee is the real ministry and

dealing with money is just a necessity. It’s ALL ministry and all of it can be

given to the glory of God.

We need all the gifts to be the Church. Paul was smart enough but it’s not rocket science; one

body, many members. Even without Paul most leaders of congregations,

both ordained and lay, eventually figure this out. We need people who know that

all things come of God and our work is to offer it back so that God can use it,

to build up the Body of Christ. God gives us all of the gifts we need – in my

work across this diocese I have come to absolutely believe this not as a pious

platitude but as my lived experience. Even our smallest congregations have what

they need, even if it feels like just a few loaves and a couple of fish. But it

is still our work to figure out how to share those gifts.

But I think there is even more

than that to “oblation.” I think we bring not only our gifts but also our hurts

and our fears and our pain. Because that, too, is a part of what makes us who

we are. Sometimes it is our vulnerabilities, rather than our strengths, that

can become the means by which others are healed and maybe even we, too, are

healed in that process. I don’t pretend to fully comprehend that. But it seems

to me that at least part of the mystery of the Cross is that what is weak and

shameful can also be transformed and used by God, too.

So I invite you to imagine

some clown pushing you down the aisle toward the altar today. And maybe you are

laughing all the way. Or maybe you are crying all the way. Or maybe it’s a

little of both. But know that the destination is a place where you can bring

your whole self and offer who you are in body, mind, and spirit. Know that it

is a place where you are welcome, where you are needed, where you are loved.

Let us pray:

Take my life

and let it be consecrated, Lord, to thee;

take

my moments and my days, let them flow in ceaseless praise.

Take

my hands, and let them move at the impulse of thy love;

take

my heart, it is thine own, it shall by thy royal throne.

Take

my voice, and let me sing, always, only, for my King;

Take

my intellect and use every power as thou shalt choose.

Take

my will, and make it thine; it shall be no longer mine.

Take

myself, and I will be, ever, only, all for thee.

Francis Ridley Havergal (1836-1879), Hymnal 707

Third Meditation –

Communion

Let us pray.

O

food to pilgrims given, O bread of life from heaven,

O manna from

on high! We hunger; Lord supply us,

nor thy

delights deny us, whose hearts to thee draw nigh.

O stream of

love past telling, O purest fountain,

wellspring from the Savior’s side! We

faint with thirst; revive us,

of thine abundance give us, and all we

need provide.

O Jesus, by

thee bidden, we here adore thee,

hidden in

forms of bread and wine. Grant when the veil is riven,

we may

behold, in heaven, thy countenance divine.

Latin, 1661, trans. John Athelstan Laurie Riley,

Hymnal 309

There is an old story about

heaven and hell that perhaps some of you have heard before. The one where both

places have the same banquet table filled with the same good things to eat. A

table filled with meats and roasted veggies and cheeses and well-aged wines and

tasty desserts.

But apparently there is a

glitch with resurrected bodies: in both places there are no elbows. There is no

way to bend your arms. So the only difference, so it goes in this story,

between heaven and hell, is that in hell the food goes uneaten because the

inhabitants there cannot figure out how to feed themselves.

In heaven they feed each

other.

Eucharist isn’t a

“self-serve” meal. We put out our hands—empty—and we are fed by God and by others.

When I was a parish priest I tried to train kids about this with moderate

success, although to be honest sometimes the adults were harder. I tried to

teach them not to grasp after the bread from the plate but to simply put out

their empty hands, and they would receive.

In our most vulnerable state,

as newborns, we rely on our mother’s milk for sustenance and nourishment. Dame

Julian of Norwich, in the fourteenth century, wrote these words in her divine

revelation:

The

mother can give her child her milk to suck, but our dear mother Jesus can feed

us with himself, and he does so most generously and most tenderly with the holy

sacrament which is the precious food of life itself… He sustains us most

mercifully and most graciously…

Her image of Christ as Mother

freaks some people out since the historical Jesus of Nazareth was a man. But Dame

Julian understood that the risen Christ who feeds us is bigger than the

historical Jesus. And the mystical Christ who gives us of his own body and

blood is beyond gender. So I think the image works, or at least it can work.

Christ is our mother, and the Eucharist is like “mother’s milk” that sustains

us for the journey.

Bread is a staple of life and

in the Bible it conveys rich meanings long before you even begin to talk about

Christ’s body. In fact sometimes I think we get ourselves stuck on Reformation

arguments about how Christ is present when we could spend a lot more time just

thinking about the miracle of bread. In the Garden of Eden, even before

disobedience, human beings are called to tend the garden. Think of a field of

wheat and what got it to that point: the preparation of the soil, the planting

of seeds, the sunshine, the weeding. It is not God alone, nor is it humans

alone. It is a wonderful, shared mystery that requires covenantal partnership.

I’ve been preaching the

Psalms in Lent and tomorrow I’ll be at the Southwick Community Episcopal

Church. They and all of you, wherever you worship tomorrow, will pray Psalm 126

which includes these lines:

Those who go out weeping, carrying the

seed,

will come again with joy, shouldering their sheaves.

will come again with joy, shouldering their sheaves.

Most of us can go for months