The Feast of St. Francis falls on October 4, but an increasing number of parishes transfer this feast to the first weekend in October and include an opportunity over the weekend for the blessing of the animals. I am at St. John's in Sutton, this weekend where the rector is The Rev. Lisa Green. Below is a copy of the manuscript for the sermon I preached there.

+ + +

For more than fifteen years I

served as the rector of the only parish in our diocese that bears the name of

St. Francis. When I went to Holden, I knew next to nothing about him,

but during my tenure we became close friends. By the time I left, I had taken to calling him "Frank."

Many of you have, I’m sure,

seen the familiar statue of St. Francis. He is pleasant enough; often some

birds are there with him or some animal is sitting at his feet. But to

encounter him in the flesh, we have to travel back to the latter days of the

twelfth century, to the Umbrian town of Assisi which is half-way between Rome

and Florence. Assisi sits on a hill and it’s obvious the roads were built long

before the automobile: so you park at the bottom of the hill and walk up. In

many ways as you walk the narrow streets it feels like you are going back in

time and one can almost imagine walking into good old Francesco, no longer a

statue but a real person in a real time and place.

In 1182, an infant boy was

baptized in the cathedral font of Assisi. His mother was a religious person who

decided to name her son after your patron saint here, John the Baptist—the one

who “prepared the way” for Jesus. He was therefore christened “Giovanni”—Francesco

was a nickname given to him by his father. In the latter part of the twelfth

century, Assisi was moving from a feudal society to a mercantile society. That

led to clashes between social classes: the old guard and the “nouveau riche”

merchants like Giovanni’s father, a cloth trader who traveled regularly on

business to France. Francesco means “little Frenchman”—presumably because of

his dad’s love for all things French.

Francis may have even traveled with his dad on business trips in his

teenage years; if he did and got to Paris then he would have seen a new

cathedral being built there that would be named for the mother of our Lord,

Notre Dame.

By all accounts, Francesco

was a spoiled rich kid. It can happen when parents are upwardly mobile, who

sometimes indulge their children so that they will have “opportunities” they

didn’t have. His father expected him to follow in his path in the family

business. Something happened, though—it’s not clear what—that led to a change

in his worldview. Some say he came down with an illness that left him bedridden

for a long period of time. In any case, he ended up in the military, wanting to

become a knight.

When someone says “semper

fi” to you, you know that they are shaped by a whole set of values that make

that person a marine. Knights in the Middle Ages were something like that, and

the equivalent of “semper fi” was the notion of chivalry. Two “core

values” for a knight were a commitment to largesse, i.e. to give freely,

and to be always courteous. Yes, sir. No thank you ma’am.

I mention that because as profoundly

shaped as Francesco would be by the gospel, these military values also played a

role in shaping who he was becoming, and in fact dove-tailed with his reading

of the gospel. Generosity and courtesy permeate the Rule of Francis: obviously

those are gospel values but they were reinforced by his training as a knight. I

suspect that the same could be said for many of us: hopefully our core values

are rooted in the gospel but our families, and our work also leave a mark.

And then Francis had this powerful

religious awakening in the church in San Damiano. While praying, he heard

Christ calling to him “Francesco, rebuild my church.” Some might call it a

“conversion experience,” but I prefer to think of such experiences as “awakenings” because they remind

us that it’s about what God was doing in his life, not the other way around.

That is to say, at that cathedral font he had already been “claimed and sealed

and marked as Christ’s own forever.” It isn’t God’s fault he was asleep to that

reality for so many years!

In any event, he finally began

to “wake up” and when he did he began to rebuild the church in San Damiano, quite

literally at first. The moment of ultimate conflict in Francesco’s life came

when his father called in the bishop, a personal friend, to talk some sense

into the boy who was beginning to take his faith too seriously. Part of what

was happening is that he was being very generous with his father’s hard-earned

money.

In the upper church in Assisi

there is a fresco of Francis and his father. I stood in front

of it for some time, trying to imagine the turmoil and the sense of shame and betrayal that

both father and son must have felt that day in the public square as Francesco

went, shall we say, “al fresco.”

There is such humanity in

that scene, long before Francis became a statue in the garden. Even if he is

canonized, I think we make a mistake if we turn Francis into the hero of this

moment and his father into the devil. I imagine his dad, especially within his

context of a changing world where there were increasing opportunities for those

willing to work hard as honestly wanting the very best for his son. The problem

is that father and son don’t see eye-to-eye on what is best. Their core values

clash and Francis has to live the life he believes God is calling him to, not

his father’s dreams.

I wonder if this isn’t a kind

of inverted story of the prodigal son: instead of the father running out to

embrace the son, Francesco’s father seems almost to be recoiling. Who is this

kid and what has happened to him? With all due respect to Francis, as a parent

I can’t help but feel some empathy for the father. That isn’t the same as

saying he was right: we raise our kids in order to let them become adults who

will find their own path to God and their own way in the world. But moments

like this one are so hard—not just for father and son (and for the bishop) but

for all the rest of us who are eavesdropping on a family matter being played

out in the town square. It’s a sad and heart-wrenching moment—at least to me it

is, even if it is also a defining moment in Francis’ spiritual journey.

So we get this very public

rift in a small town. For Francis, at the heart of the gospel was a call to

embrace poverty as a way to share in Christ’s suffering. His father simply

couldn’t understand that after all the sacrifices he had made to make life

better for his son. And so father and son go their separate ways.

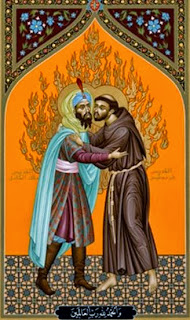

In 1219, Francis heads off to

the Middle East during the time of the Crusades. War is always hell, but the

Crusades were particularly brutal (as perhaps only religious conflicts are.)

Yet Francis goes down to Egypt to the sultan’s palace to meet with a caliph who

is roughly the same age as he is—late thirties. The Muslim leader, most likely

a Sufi mystic, is fond of religious poetry, intellectually curious, and on good

terms with the merchants of Venice. The two men meet and Francis tries to

convert him to Christianity. That doesn’t happen, but they depart in peace and

on good terms.

It is another episode in

Francis’ life worth pondering: in the heart of the Islamic world, in the middle

of the Crusades, Francis bears witness to the love of God he knew in Jesus. But

he also listens and treats the other with dignity and respect. The word crusader

literally means “he who bears the cross.” In the twelfth century and to this

very day, however, that word sends chills down the spines of people who

remember the atrocities done in the name of Christ and in the name of the

cross, especially in the Muslim world. Our language is so easily manipulated in

times of war, isn’t it? Yet Francis bore

witness in the midst of all of that to another way. He was the true crusader: for

him the “way of the cross” meant the way of mutual respect and conversation,

being an instrument of peace in a world gone mad, living with hope for the dawn

of a new day.

What lessons does

a man who lived nine hundred years ago have to teach us as twenty-first

Christians? Most of you know already of St. Francis’ love for the earth and all

creatures, great and small. He makes us want to be better stewards of God’s

good gifts, I think. One of the great ironies of my time at St. Francis is that

I am allergic to both cats and dogs and it was part of my job each year on this

weekend to bless people’s pets. I made my way through it but I came to realize

that in one sense we had it wrong: I could offer a blessing but the true spirit

of Francis is in recognizing that those cats and dogs are already a blessing in

the homes they inhabit; very much a part of the family in most cases.

But beyond that,

it seems to me that we honor Francis when we start to become crusaders in the

true sense: not as people who wield power over others but who bear the cross as

a sign of hope and of our own weakness and vulnerability. As we heard today

from St. Paul, “may we never boast of anything except the cross of our Lord

Jesus Christ.” (Galatians 6:14) We have an opportunity to be cross-bearers

whenever we stand with the poor. Like Francis, we may sometimes travel to

distant places in order to be instruments of peace and agents of

reconciliation. But like Francis, we do well to remember that sometimes the

much harder work is in reaching across the kitchen table. Sometimes the work of

reconciliation that is needed most is the work of healing the rifts that emerge

between father and son, or mother and daughter, or brother and sister.

If this congregation is

anything like the one I served, I suspect that it is pretty unlikely that

everyone here agrees on everything and holds hands at every vestry meeting and

sings kumbaya. Sometimes the work of reconciliation is hardest of all in a

parish church, which falls somewhere between family and international

conflicts. We expect that congregations will be places where love is made

manifest but the truth is that wherever two or three gather together in

Christ’s name there is sure to be conflict. But that’s never the last word. As

instruments of Christ’s peace, as people who seek more to understand than to be

understood, we also see Christ keeping his promise to be present wherever two

or three gather together as well.

What this means, I think, is

that w are called not just to pray the Prayer of St. Francis but to live

it—with God’s help. In a world where there is so much hatred and injury and

discord and doubt and despair and darkness and sadness we have our work cut out

for us. It is easy to get sucked into

all of that. But our work is clear: as bearers of the cross we are called to be

Crusaders for love and pardon and union and faith and hope and light and joy.

I like to imagine that at the

heavenly banquet, Francis and his father have bridged the chasm that divided

them in this world. And that it matters less in God’s presence who is right and

who is wrong than that we are all broken, and more than that that we are all

loved, more deeply than we can possibly imagine. In God’s presence, I imagine

that the fatted calf is killed once more and the table is set as father and son

embrace, and all is forgiven. In the meantime, we try to live the prayer of St.

Francis, finding our way into God’s presence whenever we choose to embrace our

vocation as “instruments of God’s peace.”

.JPG)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment